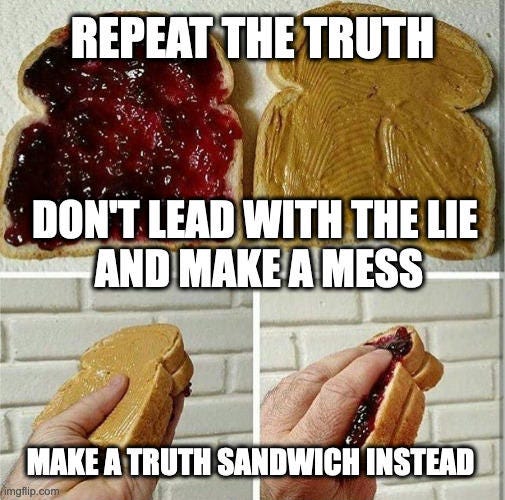

Repeat the truth, don't lead with a lie.

The "truth sandwich" means leading with the facts and repeating the correct information. It's probably the only way to debunk lies without helping to promote them.

If you lead by repeating a lie you wish to debunk — that’s the first, possibly the only thing that the audience sees or remembers1 while scrolling through social media. People may never even click to see the second tweet in a tweet thread. They may not even read the second sentence! This is why it’s so important in the current media environment to lead with the takeaway you want delivered,2 and if you’re honest of course — something truthful.

The combined psychological marketing whammy of resilient first impression,3 the halo effect,4 mere exposure effect,5 illusory truth effect,6 anchoring bias,7 and reiteration effect,8 all work together in promoting whatever gets out in front. If that something is a lie, that means promoting the very thing meant to be debunked.9 In which case it may be better not to post about it at all.

Even famous scientists, serious doctors, and experienced educators sometimes fall into bad communication habits on social media. These pitfalls are alarming. And I can’t help but notice the adversaries pushing lies never seem to mess this up. They lead with whatever they want you to believe and put it on repeat. They aren’t promoting their opposition, but they are experts in getting hate followers and rage clicks10 for loads of engagement for themselves.11 Of course the big money is behind the lies,12 and they pay for expert marketing and advertising,13 savvy influencers, and paid social media operatives who know how this psyops game is played.

I’m well aware of a lot of pandemic research and have a background in advertising art and marketing, and have spent the past couple of years reading about propaganda, disinformation, information wars, and influence strategies. But nobody is completely immune. Social media executives and tech experts often avoid social media themselves,14 and very often go out of their way to prevent their children from using it.15

The tweet that got to me was from a doctor — MD PhD who unfortunately led with the lie on the first tweet of a tweet thread. I was momentarily fooled into thinking fictitious research took place. The initial tweet went viral — hopefully because later in the tweet thread she debunks the claims. BUT THE FIRST TWEET ONLY CONTAINED THE LIE AND THE BOGUS INFORMATION — and that’s the tweet that went viral. An irony is that the doctor also publishes a debunking blog, yet seems unaware of this basic strategy for fighting misinformation. If you only saw the first tweet, especially the first sentence, you could easily have believed untrue claims. After all, an MD PhD who’s pro-vax was presenting this scary anti-vax stuff.

Several people I’ve talked to since said they would not have even seen this garbage at all — had it not been for the many twitter stars shouting it out in their timelines —dozens or more decided to prove their big shot debunking chops on this one. The tweet I saw was not the only one where someone decided to lead with the lie. Some people quote-tweeted, driving engagement. So the disinfo was repeated, highlighted, and promoted by both anti-vax AND pro-vax accounts, doing the social contagion work16 of aiding the propagandists.

Social media is addictive.17 Not just for the average user, though that’s bad enough. It also seems intoxicating to people with a lot of followers and fans — since they get tons more feedback.18 It could be people who have longed for approbation or they may have incidentally found that going viral scratches an itch maybe they didn’t know they had for reaching people with science education. Unfortunately, the algorithms involved don’t have anyone’s best interest in mind, only promoting engagement, and keeping people on the app.19 Leading with the truth and doing good public information won’t please the algorithms as much as rage fodder and fake news,20 and so there is no built-in incentive producing mechanism to teach people to do things with science communication best practices, at least not within the social media itself. In fact, quite the opposite.

Effective public health messaging will probably require mindfulness, self training, and practice with repetition by motivated scientists, doctors, public health professionals, activists, and yes “the randos” out here. Even some people with the best of intentions may not have the time to invest, or maybe not the inclination or ability. But Planck’s Principle21 isn’t the only route forward — progress does not depend solely on funerals or replacing all the pundits & public speakers — as Planck himself demonstrated,22 people are capable of change. And the “truth sandwich” is a low effort and simple method that we can all use to avoid this common pitfall. And anyone can get familiar with other marketing and influence strategies.23 This is needed against a very cognitive savvy opposition. The big shots should especially consider it because of their own potential halo effect.24 And because the side of truth, science, equity, and salubrious ideals, really needs to do better — lives depend upon it.

Don’t lead (headline, first paragraph) with the distortion or lie or rant or discreditable accusation. Go to the big picture underlying it, and synthesize a headline that shows that dynamic to the public. Ascertain the details that are likely to have precipitated this particular politician into saying this, and then present the lie in that context and debunk it. In this way, you are still reporting the truth (even when there are multiple perspectives on it), rather than amplifying (or giving oxygen to) the lie.

References:

Six Degrees Psycho-Sensory Brand-Building: The Psychology of First Impressions by Frank Schab

In fact, research tells us it only takes the duration of an eye blink to size up another person in terms of attractiveness and trustworthiness. Over the next three seconds, we form a more “complete” conclusion about a new acquaintance relating to their presumed personality and competence. Obviously, in that short a period of time, we have not really gotten to know the other person. Rather, we have used our cognitive biases and filters to form a “snap judgment” about someone, just as they have about us. Those judgments may or may not be accurate, but they endure.

@GeorgeLakoff on Twitter & FrameLab podcast on soundcloud

1. Start with the truth. The first frame gets the advantage. 2. Indicate the lie. Avoid amplifying the specific language if possible. 3. Return to the truth. Always repeat truths more than lies. Hear more in Ep 14 of FrameLab w/@gilduran76

Kahneman also clarifies how sequence matters—that is, a ‘halo effect’ increases the weight of first impressions or the first entry on a list, to the point where subsequent information is discarded. Kahneman explains this mental shortcut as a combination of the coherence-seeking System 1 thought process generating intuitive impressions, which a lazy System 2 then endorses and believes.

After people form an initial impression of someone, they try to prove it right because they don’t want to face cognitive dissonance and cognitive consistency seems like an easier option. Also, sometimes it is difficult to evaluate different qualities in isolation and people end up resorting to the more unchallenging option of assessing on the basis of the most visible trait. How the halo effect makes us use judgment heuristics or mental shortcuts, is overtly simple to understand yet we unconsciously let it cloud our views. This might tempt you to jump to the conclusion that someone smart would never fall for this. Ironically, a study shows that participants who scored higher on an IQ test were more susceptible to the halo error.

Mere Exposure Effect, by Katja Falkenbach, Gleb Schaab, Oliver Pfau, Magdalena Ryfa, Bahadir Birkan

The mere exposure effect is a psychological phenomenon by which people tend to develop a preference for things or people that are more familiar to them than others. Repeated exposure increases familiarity. This effect is therefore also known as the familiarity effect. The earliest known research on the effect was conducted by Gustav Fechner in 1876. The effect was also documented by Edward Titchener and described as the glow of warmth one feels in the presence of something familiar.

Illusory truth effect, Wikipedia

The illusory truth effect (also known as the illusion of truth effect, validity effect, truth effect, or the reiteration effect) is the tendency to believe false information to be correct after repeated exposure. This phenomenon was first identified in a 1977 study at Villanova University and Temple University. When truth is assessed, people rely on whether the information is in line with their understanding or if it feels familiar. The first condition is logical, as people compare new information with what they already know to be true. Repetition makes statements easier to process relative to new, unrepeated statements, leading people to believe that the repeated conclusion is more truthful.

Anchoring bias is a cognitive bias that causes us to rely too heavily on the first piece of information we are given about a topic. When we are setting plans or making estimates about something, we interpret newer information from the reference point of our anchor, instead of seeing it objectively. This can skew our judgment, and prevent us from updating our plans or predictions as much as we should.

The present research has demonstrated that the repetition of a plausible statement increases a person's belief in the referential validity or truth of that statement. Other research has demonstrated the sensitivity of the information processing system to the frequency variable (cf., Estes, 1976; Underwood, 1971).

CommunicateHealth: The Truth Sandwich: A Better Way to Mythbust

What’s wrong with regular old mythbusting, you ask? Just picture this chilling chain of events:

A user lands on a webpage designed to dispel myths about COVID-19.

They skim right over the word “myth” and see: “Drinking bleach can cure COVID-19.”

Then they get a text/their doorbell rings/their cat jumps onto their neck and they never make it down to the part of the page explaining that no, drinking bleach can’t cure COVID. But it sure can kill you!

This rather extreme example shows why we usually let the facts speak for themselves — and avoid restating dangerous myths in our health content. But when a truly treacherous piece of false information just keeps circulating, sometimes you’ve got to squash it head-on. Enter: the truth sandwich.

“Anger and hate is the easiest way to grow on Facebook,” Haugen told the British Parliament on Monday. In several cases, the documents show Facebook employees on its “integrity” teams raising flags about the human costs of specific elements of the ranking system — warnings that executives sometimes heeded and other times seemingly brushed aside.

The marketing term “effective frequency” refers to the idea that a consumer has to see or hear an ad a number of times before its message hits home. Essentially, the more you say something, the more it sticks in — and possibly on — people’s heads. It doesn’t even have to be true — and that’s the problem. What advertisers call “effective frequency,” psychologists call the “illusory truth effect”: the more you hear something, the easier it is for your brain to process, which makes it feel true, regardless of its basis in fact. “Each time, it takes fewer resources to understand,” says Lisa Fazio, a psychology professor at Vanderbilt University. “That ease of processing gives it the weight of a gut feeling.” That feeling of truth allows misconceptions to sneak into our knowledge base, where they masquerade as facts, Fazio and her colleagues write in a 2015 journal article.

The Lever: How Dark Money Shaped The School Safety Debate by Walker Bragman & Alex Kotch

But the end of school masking is also in part due to a campaign by right-wing business interests, including the dark money network of oil billionaire Charles Koch, to keep the country open for the sake of maintaining corporate profits. These interests have been meddling in the education debate, first pushing to reopen schools and then fighting in-school safety measures, even as COVID case numbers were rising and children were ending up in hospitals. For nearly two years, these groups have been promoting questionable science and creating wedges between parents, teachers, and administrators in order to get America back to work — even at the risk of the nation’s children.

State Government Leadership Foundation (SGLF) Feb 9, 2022 @theSGLF on Twitter

Our latest ad is making an impact and liberals are now agreeing with what conservatives have been saying all along: mask mandates do more harm than good.

"The thought process that went into building these applications, Facebook being the first of them, ... was all about: 'How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible?'" "And that means that we need to sort of give you a little dopamine hit every once in a while, because someone liked or commented on a photo or a post or whatever. And that's going to get you to contribute more content, and that's going to get you ... more likes and comments." "It's a social-validation feedback loop ... exactly the kind of thing that a hacker like myself would come up with, because you're exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.""The inventors, creators — it's me, it's Mark [Zuckerberg], it's Kevin Systrom on Instagram, it's all of these people — understood this consciously. And we did it anyway."

The people who are closest to a thing are often the most wary of it. Technologists know how phones really work, and many have decided they don’t want their own children anywhere near them. A wariness that has been slowly brewing is turning into a regionwide consensus: The benefits of screens as a learning tool are overblown, and the risks for addiction and stunting development seem high. The debate in Silicon Valley now is about how much exposure to phones is O.K. “Doing no screen time is almost easier than doing a little,” said Kristin Stecher, a former social computing researcher married to a Facebook engineer.

This propaganda feedback loop demonstrates the power of inundation, repetition, emotional/social contagions, and personality bias confirmations, as well as demonstrating behaviours of people preferring to access entertaining content that does not require ‘System 2’ critical thought. Audiences encountered multiple versions of the same story, propagated over months, through their favoured media sources, to the point where both recall and credibility were enhanced, fact-checkers were overwhelmed and a ‘majority illusion’ was created.

Vox: How technology is designed to bring out the worst in us By Ezra Klein

The main thing is to say it’s not by accident. It’s happening by design. Think of it like the Truth campaign with cigarettes. If you remember the 1990s TV ads, it was not saying, “Hey, this is going to have this bad health consequences for you if you smoke.” That feels like someone is telling you what to do. The Truth campaign was about telling you the truth about how they design it deliberately to be addictive. The simplest example I always use is Snapchat, which is the No. 1 way that all teenagers in the US communicate. It shows the number of days in a row that you sent a message to your friend. That’s a persuasive and manipulative technique called “the streak.”

People: She's Back! Kendall Jenner Returns to Instagram One Week After Deleting Account

“I just wanted to detox,” Jenner told DeGeneres. “I just wanted a little bit of a break. I would wake up in the morning and look at it first thing, I would go to bed and it would be the last thing I looked at. I felt a little too dependent on it so I wanted to take a minute.”

Often compared to Big Tobacco for the ways in which their products are addictive and profitable but ultimately unhealthy for users, social media’s biggest players are facing growing calls for both accountability and regulatory action. In order to make money, these platforms’ algorithms effectively function to keep users engaged and scrolling through content, and by extension advertisements, for as long as possible.

As it turned out, tweets containing false information were more novel—they contained new information that a Twitter user hadn't seen before—than those containing true information. And they elicited different emotional reactions, with people expressing greater surprise and disgust. That novelty and emotional charge seem to be what's generating more retweets.

Planck's principle From Wikipedia

”An important scientific innovation rarely makes its way by gradually winning over and converting its opponents: it rarely happens that Saul becomes Paul. What does happen is that its opponents gradually die out, and that the growing generation is familiarized with the ideas from the beginning: another instance of the fact that the future lies with the youth.” — Max Planck, Scientific autobiography, 1950, p. 33, 97

“A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.” - Max Planck. In point of fact, Planck was an exception to his own 'principle', many of his most illustrious colleagues were too, and the relativistic implications which Kuhn and others have drawn from it are diametrically opposed to Planck's specific comments on that subject. In short, Planck's 'principle' was a mere obiter dictum which reflected neither his most fundamental beliefs nor the scientific practice of himself or the great men around him. Max Planck's most outstanding contribution to science, his quantum theory of 1900, required him to accept Boltzmann's constant and the latter's statistical interpretation of the second law of thermodynamics, which Planck had specifically opposed for over twenty years, in fact since his own doctoral dissertation of 1879.

Playmaker Precision Influence Strategy: Taxonomy of Influence Strategies

The Taxonomy of Influence Strategies is the front door to a patented, precise and proven ontology that identifies, describes and classifies the fundamental units of advocacy and persuasion (aka, influence or social plays).

The halo effect is a cognitive bias that claims that positive impressions of people, brands, and products in one area positively influence our feelings in another area.

Thank you for this, Chloe! It is good to know/be reminded of this as both a reader and a poster, and I will definitely double-check myself and others with this information. I really feel it is an important message.